Failing Well, Not Fast

This article was originally published here by Fuller de Pree Center

Someone asked me once, “Why are you afraid to fail?” I remember wading through a bunch of half sentences until I admitted, “I don’t want to fail because I’m afraid of who that means I am. Basically, my identity is at stake.” Even though I know that my being is more important than my doing, what I do is still really important to me. While I know that failure is not only permissible but also important for my creativity as an entrepreneur, it does not make it any easier.

I have also learned that my own capacity to tolerate failure is linked with how personally invested I am. In other words, if I am only a little bit invested in something, failure is no big deal. I’m happy to fail and iterate all day long. But, the more I care about in an idea, a relationship, or a goal the more painful it is when things do not work out. Because my work as an entrepreneur is birthed out of passion and personal interests, failure often feels really personal. When I experience failure in areas that I’m really invested in, each failure feels like a type of death.

I am finding that in order to deal with failure, I have to learn to deal with death. Death is hard, painful, and scary. I find it difficult to sit with the pain that seeps in when things don’t turn out the way I imagined or when I let people down. But, understanding failure as a type of death also gives me permission to sit in the uncomfortable space that my soul craves in the midst of chaos—the grief that loss requires.

Many of my favorite scholars talk about the need to fail fast, rightfully citing that the more entrepreneurs iterate, the quicker we are able to both innovate and make an impact. But for me, just as important as failing fast, is failing well. To rush past the pain of failure would be to cheat the learning it holds.

I recently conducted my dissertation research on the formative practices of entrepreneurs. Across the board, I heard stories of successful people intentionally dealing with death—the death of expectations, ideas, and relationships. One person explained how he had to deal with the lack of large-scale growth he had once imagined. Another told the story of a key-hire going wildly wrong leaving the company with falling profits and a bruised work culture. And still another told me the heartbreaking story of how she realized she was not cut out to be a CEO. As each of these people told me their stories I was reminded that failing well is less about fast iteration and more about grieving a painful death.

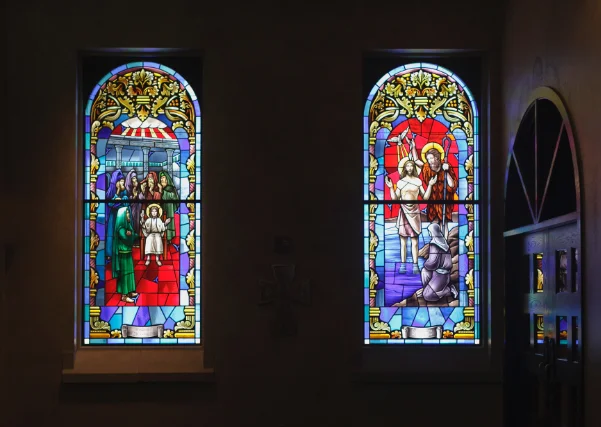

As Christians, our hope lies in the new life that comes through death. In other words, in order to fully appreciate the Resurrection of Christ and we must also sit with the death of Christ. We must let ourselves feel what is uncomfortable, and not rush to move past it. And, as we participate in God’s Kingdom here on earth, our hope lies not only in the cumulative event of Resurrection, but also the smaller, daily “small r” resurrections. And just as with Jesus, new life requires death, hope comes through sorrow, and success is birthed from failure.

So, how do we navigate these failures in a way that allows for resurrection life? I have found the practice of lament to be particularly helpful in my work as an entrepreneur. I like to think of lament as a structure to shake my fist at God, a way to tether myself to structure in the midst of chaos. I learned a long time ago that God can handle my anger and my pain, and that cross of Christ is not a place reserved only for when I succeed. Rather, the cross of Christ is a place where death is acknowledged and held.

Specifically, the Psalms offer a framework for engaging God as we seek to fail well. A Psalm of Lament has five key parts: an opening address (who you are talking to), the complaint (what you’re upset about), confession of trust (telling God where your trust lies), petition for help (asking God for help), and the vow of praise (praising God).

Here’s how the structure plays out in Psalm 22:

The Opening Address, “My God, my God” (22:1a)

The Complaint “Why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning? (22:1b)

Confession of Trust, “yet you are holy, enthroned on the praises of Israel. In you our ancestors trusted; they trusted, and you delivered them. To you they cried, and were saved; in you they trusted, and were not put to shame.” (22:3-5)

Petition for help: “Do not be far from me, for trouble is near and there is no one to help. (22:11,29)

Vow of Praise: “From the horns of the wild oxen you have rescued me. I will tell of your name to my brothers and sisters in the midst of the congregation I will praise you.” (22:21a-22)

Many of us value tools that help us grieve personal loss and crisis in our world. But, we also need ways to help frame our vocational identities, especially in the midst of failure. It is through facing small deaths that resurrection takes shape in my work as an entrepreneur.

I encourage you to write your own Psalm of Lament around a vocational failure. It can be around the work God has called you to in your home, office, or community. Over the last few years, I have asked hundreds of people to do this exercise. And at first, many people are hesitant. Some even skip over it. Dealing with any type of death is tough. But most people who engage are surprised at what comes up and appreciate the structured space to sit with hard things around their vocation. One woman told me, “At first this felt kind of weird. I felt uncomfortable. But then I started to hear myself talk about some really surprising things. I started to really hear my own voice.” I hope that it can be a tool that helps you hear yourself talk to God.

Related articles

——

[ Photo by Atharva Tulsi on Unsplash ]

“Hurt is going to happen.” With those five words, I was reminded once again of why we so separately need Jesus. We’re all going to fail. And sometimes, it’ll be big. And every time it will hurt.